Time Encoding in the Lateral Entorhinal Cortex

A presentation of the 2025 Science paper shows how the Lateral Entorhinal Cortex (LEC) encodes time via two mechanisms. A continuous 'slow drift' and abrupt 'shifts' at event boundaries.

Original Paper: Event structure sculpts neural population dynamics in the lateral entorhinal cortex

Core Idea

Episodic memory requires encoding both “what” happened, “where” it happened, and “when” it happened. While we know the Medial Entorhinal Cortex (MEC) encodes space (via grid cells), how the brain encodes time has been a mystery. This paper proposes that the Lateral Entorhinal Cortex (LEC) provides the temporal context for episodic memory. It does this through two distinct population-level dynamics:

- A continuous “slow drift” of neural activity that intrinsically tracks the slow passage of time.

- Abrupt, rapid “shifts” in neural activity that segment continuous experience into discrete events, occurring at “event boundaries”.

Summary of the Paper

The LEC’s Continuous “Slow Drift”

- Using dimensionality reduction (LDA) on neural recordings, the authors found that while MEC and CA1 activity remained stable, LEC activity showed a clear, continuous, and non-repeating trajectory (a “drift”) as time passed.

- This drift was not an artifact of the analysis, as it was also present in the full high-dimensional data.

- To test if the drift is an intrinsic clock or driven by external stimuli, researchers recorded rats during REM sleep. The temporal drift persisted during sleep, closely matching the drift seen when the animals were awake and foraging. This strongly suggests the LEC contains an intrinsic mechanism for tracking the flow of time.

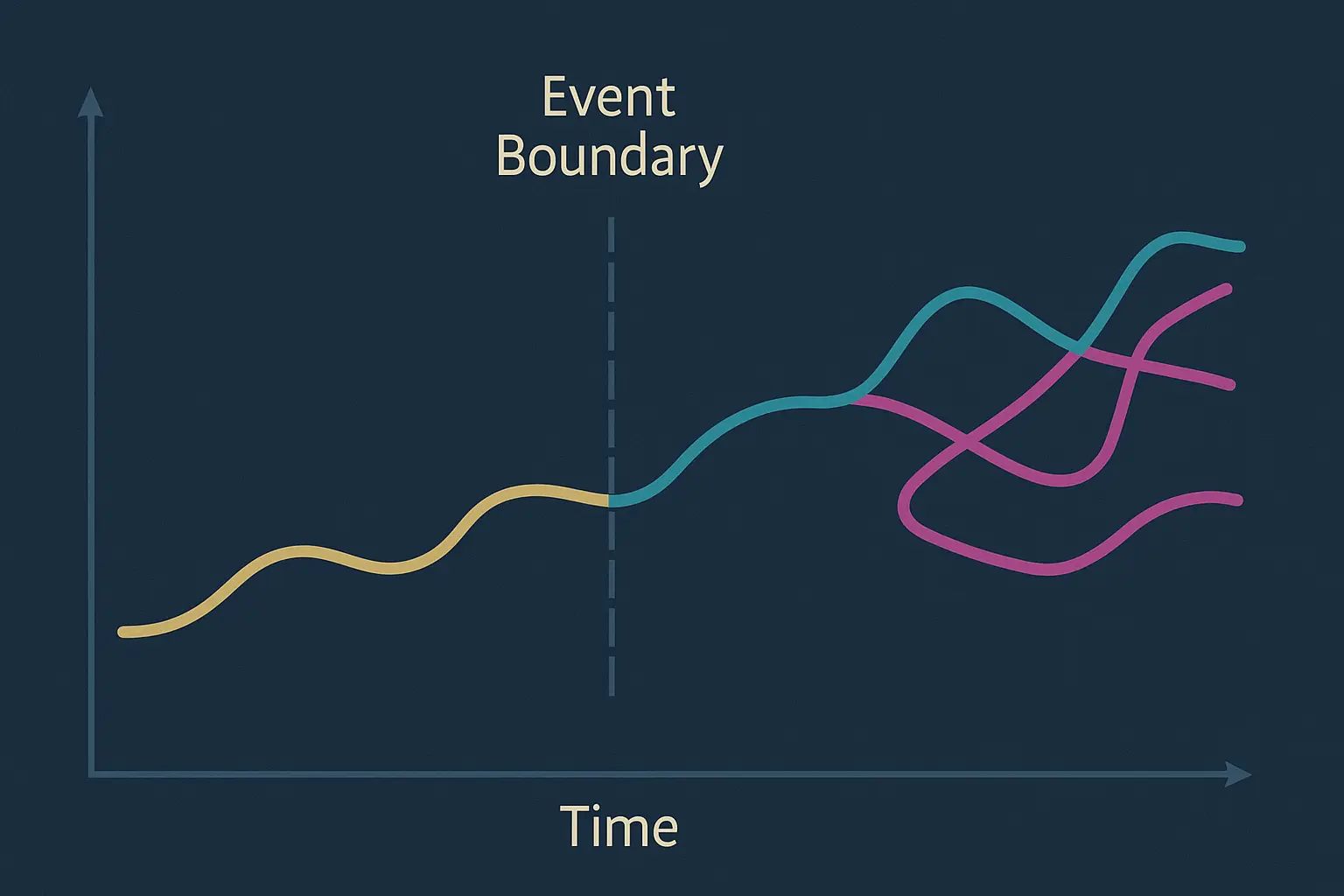

Event Boundaries “Shift” the Trajectory

- The paper then explores how “event boundaries” (like starting a task or getting a reward) affect this continuous drift.

- These boundaries don’t reset the clock, but instead cause an abrupt acceleration and deceleration of the neural trajectory—a “shift”.

- Task-Relevance is Key: These shifts are not triggered by all sensory changes.

- In a Figure-8 maze, the shift happened reliably just before and after the rat received a reward.

- In an odor-sequence task, a novel odor (on its first presentation) caused a shift, but a familiar odor did not, even though it was a sensory change.

- This shows that shifts are tied to task-relevant, significant, or novel events, not just simple sensory input.

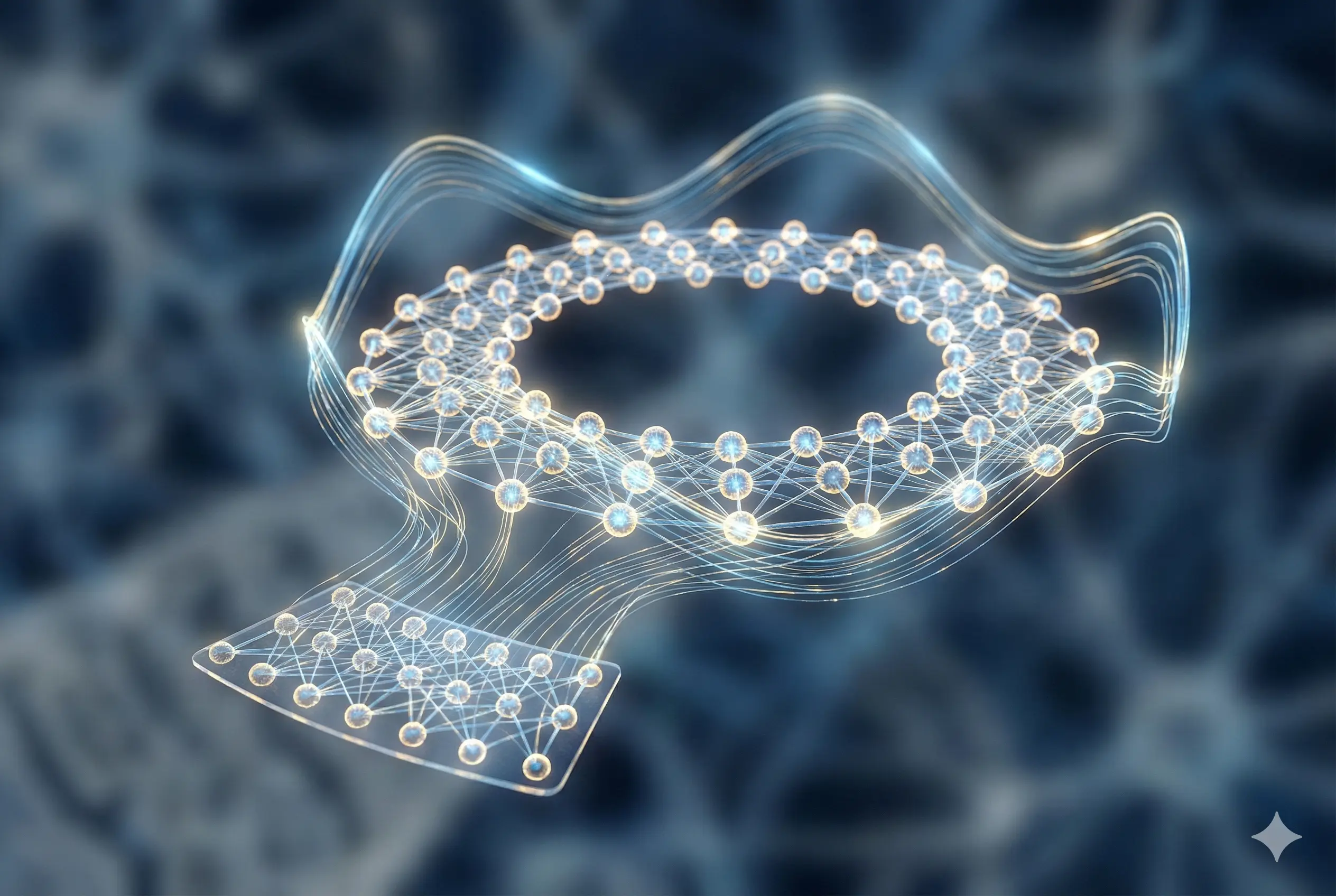

Hierarchical Time Encoding

- The LEC population encodes multiple timescales simultaneously.

- The analysis revealed two orthogonal (independent) axes of time-coding.

- One axis encoded “fast time” (seconds within a single trial).

- A second, orthogonal axis encoded “slow time” (minutes, tracking which trial number it was in the overall session).

- This suggests a hierarchical system where event boundaries (shifts) are nested within a continuous temporal context (drift).

Mechanisms: Slow and Fast Dynamics

- The paper separates the mechanisms for the two phenomena:

- Drift (Slow): The continuous drift is driven by a sub-population of neurons with very high firing variability (high Fano factor) and slow-changing dynamics. Removing just the top ~30% of these high-variability neurons was enough to completely stop the drift.

- Shifts (Fast): The abrupt shifts are driven by a different set of neurons that fire in fast, transient bursts precisely at the event boundary. These neurons fire in unique, variable patterns for each specific event, creating a “barcode” or “time stamp” that makes each boundary neurally distinct.

Key Discussion Points

LEC Drift vs. Hippocampal Time Cells: The group discussed the difference between the LEC’s “drift” and classic “time cells” found in the hippocampus. The consensus was that they are complementary:

- LEC Drift is a continuous, intrinsic, high-dimensional representation (a “basis”) for time.

- Time Cells are discrete, event-locked representations (e.g., “5 seconds after the bell”).

- The hypothesis is that the hippocampus reads out the continuous LEC drift to create discrete time cells, much like it reads out MEC grid cells to create place cells.

MEC as Fourier, LEC as Laplace: A major theoretical idea discussed was that the entorhinal cortex provides mathematical bases for the hippocampus.

- MEC (Space) acts like a Fourier Transform, breaking down 2D space into periodic grid patterns.

- LEC (Time) may act like a Laplace Transform, breaking down time into a set of basis functions with different exponential decay rates. This would allow for a robust, multi-timescale representation of the past.

Are the Findings an Artifact? A critical discussion focused on the methods. The authors used specific parameters (e.g., 50% variance for PCA, 1-minute and 10-minute time epochs). The presenters noted these are somewhat arbitrary, and it’s possible that changing these parameters (e.g., to 30% variance or 2-minute epochs) could make the results disappear, or even appear in the MEC instead.

What Defines an “Event”? The discussion explored what the LEC considers an “event boundary”. The data from the odor task and novel object task suggests it’s not just any sensory change. The event must be task-relevant (like a reward) or novel. This implies a top-down filtering mechanism that determines which moments are “significant” enough to be segmented by a neural “shift”.